The VR spaceship post lead me to recognize that I haven't said too much about what I do outside of my professional work Having just wrapped up a deep dive into the subject of wizards, it may be a good time to segue into talking about the world of pen-and-paper RPGs.

I had dabbled in pen-and-paper adventures back in high school, but I wasn't part of a long-running campaign until I joined one with my friends from 360Ed. I must say, if you ever get the chance to have a friend who is a professional game designer run your RPG adventure, definitely jump on that.

Meanwhile, I was encouraged to try running some content of my own with some friends on an internet forum. Oh, how long ago was that, then? Looking at the map files, this was around 2009, so still in the midst of the 360Ed era, for me. I guess even then, forums in general were kind of on their way out. The group did eventually to Skype and eventually Discord as the landscape of the Internet shifted.

But setting aside the changing landscape of the real digital world, let's talk about the imaginary world I attempted to create. It was suggested that I "D&D in Space" as a sort of modern take on Spelljammer, and despite knowing very little about that classic setting, I used that as a jumping-off point for our first adventure.

I would up creating a spatial anomaly containing a floating archipelago of locations that for one reason or another had become lost in time and space, such as a D&D take on the Bermuda Triangle, a sinister castle banished by a party of heroes, and a city erased by a time paradox.

I illustrated this fairly simply in a Javascript-based map tool called . . . oh, just MapTool, actually. Here is one of one of the islands as an example.

I had dabbled in pen-and-paper adventures back in high school, but I wasn't part of a long-running campaign until I joined one with my friends from 360Ed. I must say, if you ever get the chance to have a friend who is a professional game designer run your RPG adventure, definitely jump on that.

Meanwhile, I was encouraged to try running some content of my own with some friends on an internet forum. Oh, how long ago was that, then? Looking at the map files, this was around 2009, so still in the midst of the 360Ed era, for me. I guess even then, forums in general were kind of on their way out. The group did eventually to Skype and eventually Discord as the landscape of the Internet shifted.

But setting aside the changing landscape of the real digital world, let's talk about the imaginary world I attempted to create. It was suggested that I "D&D in Space" as a sort of modern take on Spelljammer, and despite knowing very little about that classic setting, I used that as a jumping-off point for our first adventure.

I would up creating a spatial anomaly containing a floating archipelago of locations that for one reason or another had become lost in time and space, such as a D&D take on the Bermuda Triangle, a sinister castle banished by a party of heroes, and a city erased by a time paradox.

I illustrated this fairly simply in a Javascript-based map tool called . . . oh, just MapTool, actually. Here is one of one of the islands as an example.

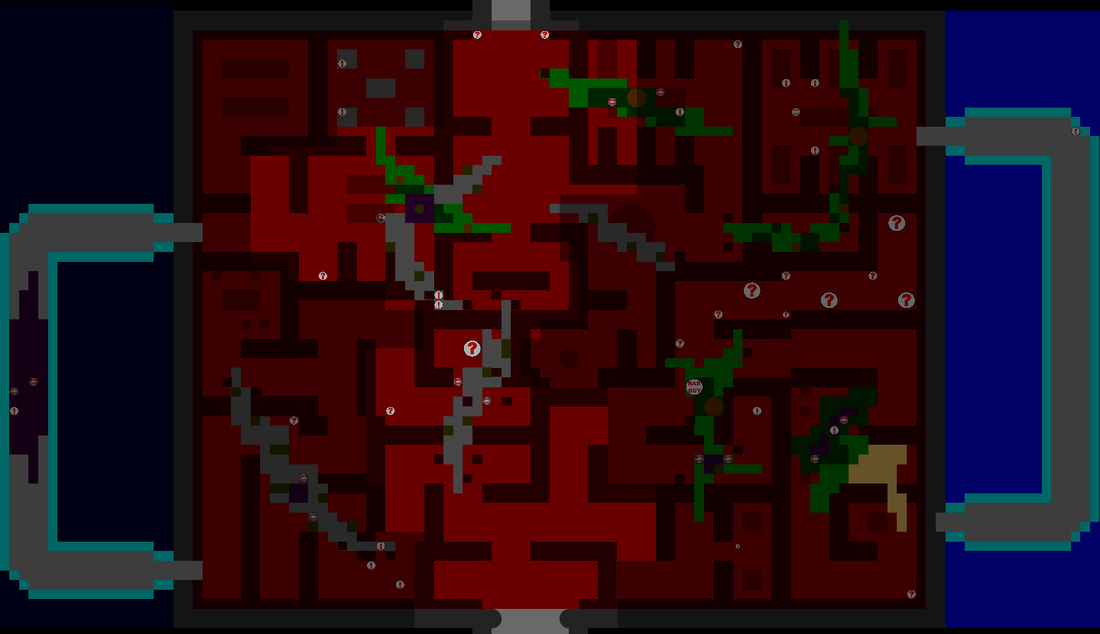

Dungeons were a similar mix of primary colors and basic circular iconography. The MapTool provided assistance with lighting and vision while I moved around big circular icons representing characters and points of interest.

Here is one of the more elaborate dungeons, in which an underwater shrine has been torn at by spatial anomalies that have caused it to intersect with other environments.

Here is one of the more elaborate dungeons, in which an underwater shrine has been torn at by spatial anomalies that have caused it to intersect with other environments.

However, I wanted to experiment with something a bit more visually clear and fun. I didn't have a big box of figure tokens or even a collection of fantasy artwork, but I did have a fairly extensive knowledge of retro video games, which lead to an idea.

Near the climax of 'season one' of the campaign, the party invaded the fortress of the primary antagonists. One of the villains had created an intelligent magical artifact that had unexpectedly gained self-awareness during a prior story arc. They then sought to re-create this project in order to create a sort of magic-based AI to control systems within their fortress.

When the party stepped onto what appeared to be some kind of Teleporter pad to travel to the next floor of the ship, they instead found themselves pulled into the D&D equivalent of a Tron-like scenario, in which they were transported it the Magic AI's realm of information.

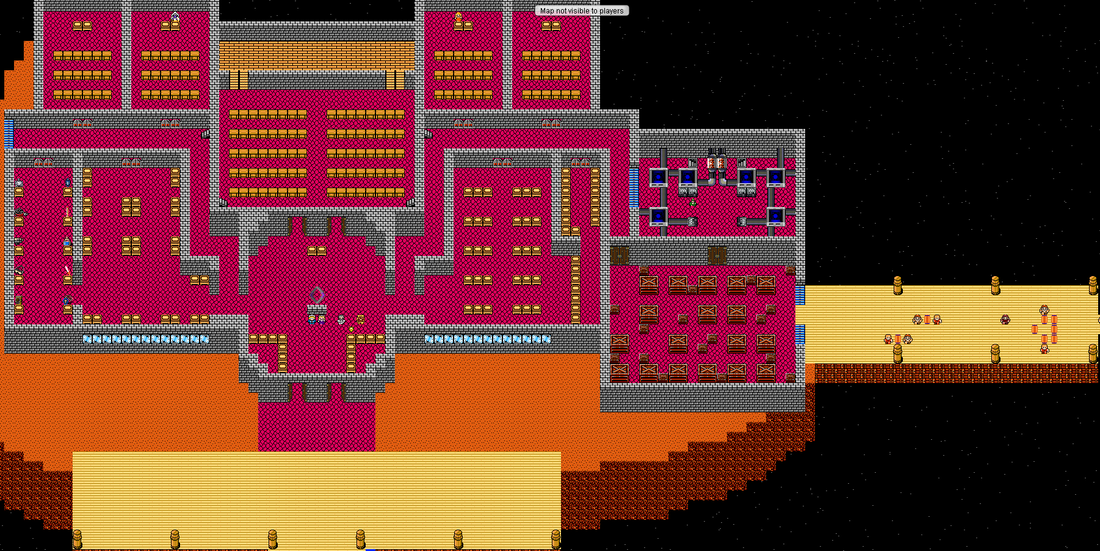

I used this as an excuse to re-create a simplified caricature of the campaign thus far using retro video game graphics to represent the world as seen via this information-based magical creature.

Near the climax of 'season one' of the campaign, the party invaded the fortress of the primary antagonists. One of the villains had created an intelligent magical artifact that had unexpectedly gained self-awareness during a prior story arc. They then sought to re-create this project in order to create a sort of magic-based AI to control systems within their fortress.

When the party stepped onto what appeared to be some kind of Teleporter pad to travel to the next floor of the ship, they instead found themselves pulled into the D&D equivalent of a Tron-like scenario, in which they were transported it the Magic AI's realm of information.

I used this as an excuse to re-create a simplified caricature of the campaign thus far using retro video game graphics to represent the world as seen via this information-based magical creature.

Taking assets from Dragon Quest, Final Fantasy, and many others, I assembled this map, which was a big hit with the players. It was both visually interesting, and it was a fun way to look back on where we had been as this story neared its' conclusion.

Oh yes, the higher fidelity room there was hidden from the players. There were a number of secret back door terminals they had to find in order to escape. They were all hidden in very classic sorts of retro-game ways, so everyone was quick to play along and find them all.

Oh yes, the higher fidelity room there was hidden from the players. There were a number of secret back door terminals they had to find in order to escape. They were all hidden in very classic sorts of retro-game ways, so everyone was quick to play along and find them all.

I liked the clarity afforded by the visual style so much, I wanted to keep using it outside of this magical information world, but I needed a way to show that our heroes had returned to reality.

I decided to borrow some 16-bit assets from Final Fantasy IV to create the remainder of the final dungeon, in part because FF4 contains both assets for a fantasy castle and a giant ominous computer core that can be easily assembled.

I decided to borrow some 16-bit assets from Final Fantasy IV to create the remainder of the final dungeon, in part because FF4 contains both assets for a fantasy castle and a giant ominous computer core that can be easily assembled.

When it came time for our next adventure, the retro style returned in full force, resulting in amusing things like a school of teleportation magic with Mega Man boss doors outside it's lab. Eagle-eyed viewers may also be able to spot some NPCs who are clearly Touhou Project characters.

Since the NPC tokens were basic 16x16 sprites, I would often modify and customize the retro assets to give characters more unique tokens. While I'd never claim the title of pixel artist, dabbling in these basic edits and learning the actual palette limitations of the NES would inspire me to create placeholders for all the projectiles and explosions in the final Phyken Media prototype game.

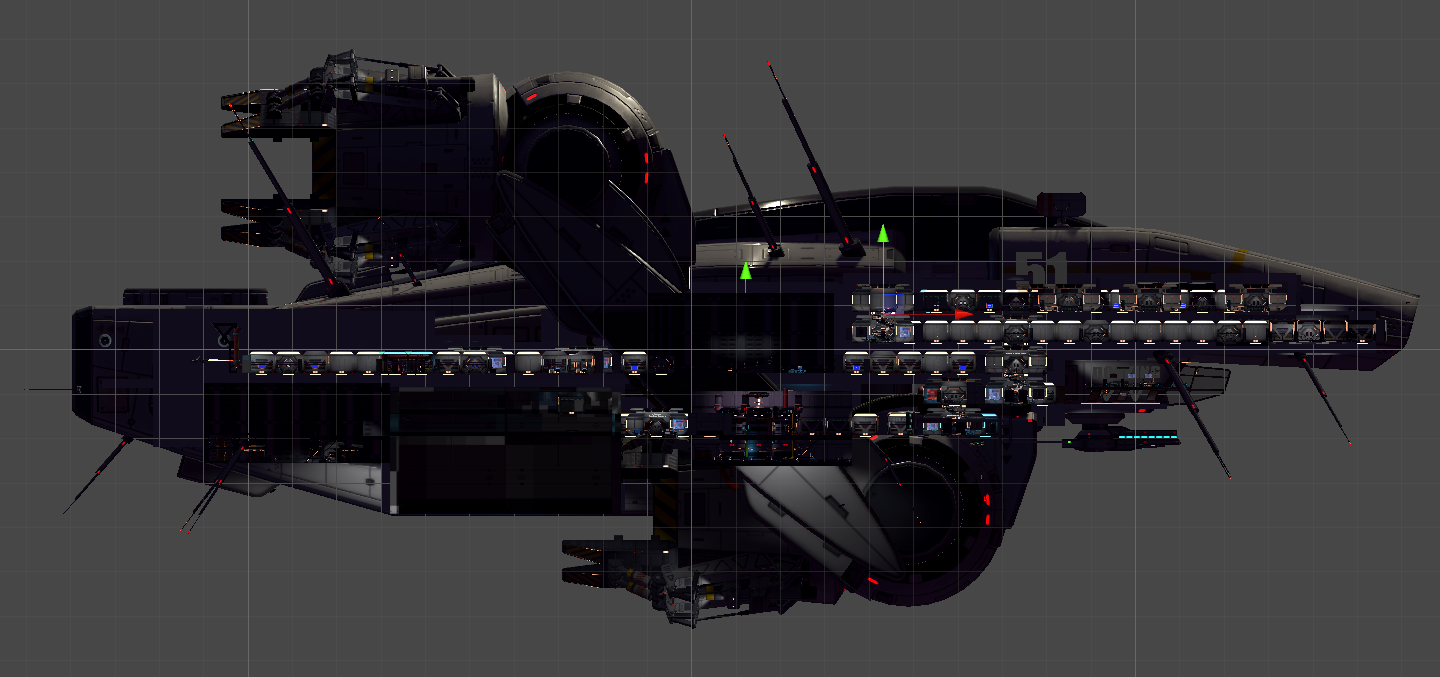

Years later, I would try an even more elaborate visual style in an adventure that was even more strongly influenced by video games, but I'll save that tale for another time.

Since the NPC tokens were basic 16x16 sprites, I would often modify and customize the retro assets to give characters more unique tokens. While I'd never claim the title of pixel artist, dabbling in these basic edits and learning the actual palette limitations of the NES would inspire me to create placeholders for all the projectiles and explosions in the final Phyken Media prototype game.

Years later, I would try an even more elaborate visual style in an adventure that was even more strongly influenced by video games, but I'll save that tale for another time.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed